In an audio editor, when you cut out a section of audio (top), the boundaries of the edit automatically come together (bottom) Still, it’s wise to make a safety copy of whatever you’re working on before you start the edit. It’s a little misleading, because today’s audio editors have multiple levels of undo, so you can usually revert to a previous state if you make a mistake (before you save and close the file, that is). If you’re working on, say, cleaning up start and end points on a group of mixes, and you have 10 or 12 songs to deal with, it can be a lot quicker to do the trimming in your audio editor, rather than importing the files to your DAW, editing them, and then waiting as you bounce each one to disk. If you’re doing post-production editing on a long-form project, for instance a video soundtrack or podcast, where you have to do a large number of edits, you can save significant time working in an audio editor.ĭon’t let the term “destructive editing” scare you off. Whereas in a DAW, after you’re done editing you have to bounce (aka “export”) your files to disk, which is usually done faster than realtime, but still takes a lot more time than a save does in a digital audio editor.

But the most important answer is that for certain types of tasks, destructive editing can be a big time saver. You do your edits, hit save, and they’re written to the file. You might wonder why you would want to use destructive editing in an audio editor when you can accomplish the same things non-destructively in your DAW? There are a couple of reasons: First, some processes, like time stretching and pitch transposition are destructive by their nature.

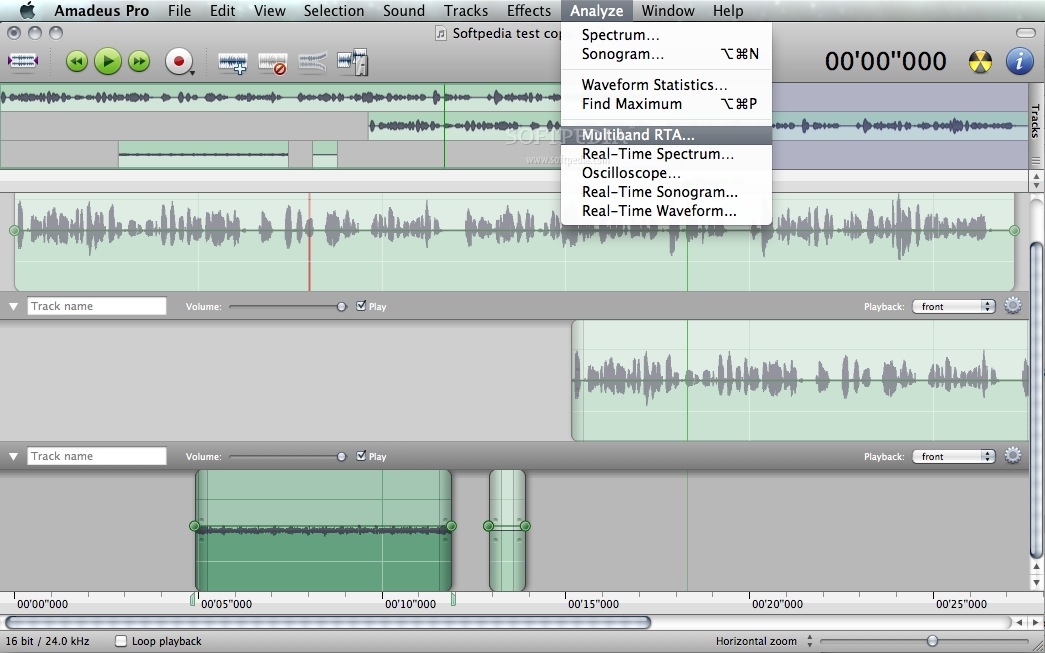

#Declicking in amadeus pro pro#

Some DAWs do let you selectively apply destructive editing (for example Pro Tools’ AudioSuite processing), however. Many DAWs let you export your file temporarily to an external editor where you apply destructive processes - for example normalization - and then the processed file is reimported back into your DAW session. While it sounds ominous, destructive editing means that your edits are actually applied to the audio file itself, whereas in a DAW, which uses non-destructive editing your edits are stored as instructions that tell the software what parts of the audio to access on your hard drive and what to do with it, but they don’t impact the original audio file.ĭAW editing is, for the most part, non-destructive. One of the main reasons that’s true is that audio editor applications typically employ destructive editing, rather than the non-destructive editing used by your DAW. The biggest advantage of audio editors is that for certain types of tasks, they’re more efficient than your DAW. Master of destruction Audacity is a freeware digital editor that comes with a collection of effects including denoising and declickingįor the most part, you use a digital audio editor when editing or processing individual mono or stereo files - often stereo mixes - although there are multitrack audio editors, as well.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)